Revision: A Case Study

When we talk about the creative process, it’s easy to focus on the broad strokes — inspiration, integrity, community, message. After all, these are the things that keep us making art, the things that get us up in the morning and keep us up at night: creating, battling ego, seeking out kindred spirits, screaming into our pillows.

But if you make art, you know it is a discipline of constant refinement, shaping, polishing and sharpening. Adding and taking away. A voice must be honed to be effective.

Two of the most instructive books I own on the craft of revision are books of poetry. The first is an edition of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, edited by Barry Miles, that contains a facsimile of Ginsberg’s original 1955 drafts, and all the variant versions with notes, edits and correspondence. The second is Poems, by Elizabeth Bishop, with its appendix of some 70 pages of unpublished manuscript poems, showing Bishop’s handwritten originals and corrections.

Whether Bishop, the queen of the precise image, is changing “worshippers, holding hands, dressed in white” to “worshippers in white,” or Ginsberg, the king of the meandering phrase, is changing “ghastly industries” to “demonic mills” and deleting multiple lines with bold pencil marks, we see master artists at work, chipping away a word at a time. Over long periods of time.

Originally, I’d planned to build a case study from Howl or one of Bishop’s manuscripts, but I’m leery of copyright infringement and am nowhere near knowledgeable enough on either to weigh in with intelligence.

There’s really only one artist whose work I know thoroughly, and whose permission I can secure to share their in-progress work. And that’s … little old me.

I’ll be the guinea pig for this case study. Please note that I do this with more anxiety than excitement. As you, dear artist-reader know, the showing of unfinished work is akin to pinning your underwear to a clothesline. In Times Square.

Inspired by this week’s interviewee, Matthew Ryan, who released a progress single with multiple demo versions of his song “Rivers,” I chose to use three iterations of one poem as a case study in revision.

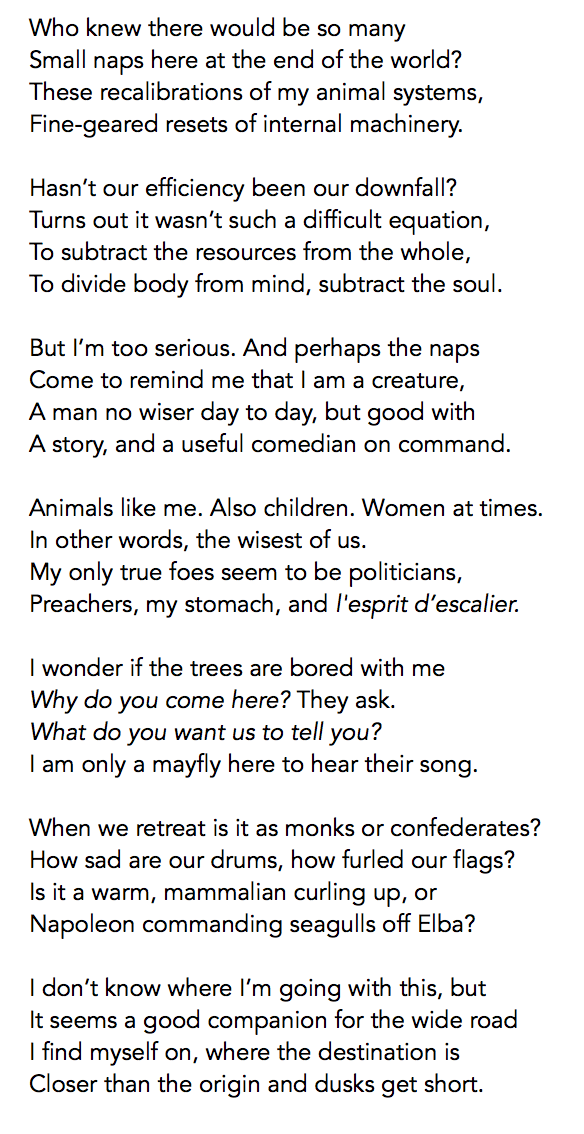

The first version of this poem is actually a second or third initial pass, quickly touched up after an initial burst of inspiration. Written on a short retreat to the woods, it begins as a dialogue with the feelings of doom and disappointment that have accompanied the spring and summer of 2020. Then, it begins to meander.

At first blush, I was in love with this poem in the way we’re all in love with a new piece. I congratulated myself on being funny and deep, on somehow addressing social issues while connecting with nature. Hell, I had a Napoleon on Elba reference. Deep stuff.

Right.

First, it’s essentially prose. I try to enforce a rule with myself that if something can be said in prose, it should be. A poem should be a thing you can’t communicate in any other format. This was essentially the first draft of an essay with lots of line breaks.

Second, it was slack. Too many words, too much passive voice. A poem should be distilled. This was a stew. There were too many ideas bouncing around for seven stanzas.

Finally, what was I really trying to get at? What was I gnawing on? Anxiety at the state of the world? Examination of my own internal response to the state of the world? What was I looking to nature for — reassurance (“animals like me”), scale (“I am only a mayfly”), perspective (“I am a creature”)?

So I took the knife to it.

The focus of the poem became apparent to me this time while I edited. This seemed to be about going to nature to find a long-scale perspective on a short-scale human moment, and the tension between the natural and the socialized — that is, between animals and humans who believe themselves to be more than just animals with vices.

The poem naturally turned itself away from Napoleon, from self-conscious references to multiple meanings of “retreat.” Instead, it went more honestly inward, both into the self and into the forest.

But, what’s with the “you” in the last stanza? Where did that come from? Was this a cheap and easy way to bring the salt image back around — was I making an amorous object a human salt lick? Ew.

Also, the reference to living “to be 1,000 years old” is dishonest. I have no interest in that. As an attempt at conveying time at scale, it’s honest but clumsy.

Finally, there are two sticking points to me with this second iteration. It is too self-referential, and it has no consistent rhythm. A strength of the first version is that it had an interesting (to me, at least) rhythm of long, conversational passages punctuated with brief, percussive ones. It felt like what it was — a person talking to themselves in the woods. This version felt choppy and rhythmically unintentional … because it was.

And so, I gave myself the incredibly freeing and instructive gift of restrictions.

I cut the form from arbitrary four-line stanzas to couplets, and allowed myself 10 syllables per line (without worrying about meter). This change immediately cut passive voice and extraneous phrases. It forced me to dig to the marrow of the line.

Now, we have shaved the poem from 28 lines to 18, and from a first draft count of 219 words to a third draft of 144. Of course, brevity isn’t the goal with this poem. It’s not advertising copy. But it does provide a good marker of effective concision.

The language is both more precise and more metaphorical now. The couplet —

Animals who think they’re not animals.

Make for an efficient apocalypse

replaces the original stanza —

Hasn’t our efficiency been our downfall?

Turns out it wasn’t such a difficult equation,

To subtract the resources from the whole,

To divide body from mind, subtract the soul.

It means (to me) the same thing, and also gives the reader room to breathe — some wiggle room to interpret the lines in a way that embraces how they feel here at the previous couplet’s “end of the world.”

Rhythmically, this poem is more sophisticated than the earlier incarnations. The 10-syllable lines help, but it’s ultimately due to shaping. Lines that are self-referential and that refer to human civilization are choppy with short phrases. Lines about nature and reconnecting or melding with nature are smoother with longer, smoother sounds.

The earlier versions toyed with repetition, but with no real strategy behind that. Here, repetition frames the poem, opening it, closing it and transitioning two three-couplet sections from one section focused on the human to the other focused on the natural.

The meaning of the end, I’ll leave to your interpretation.

The poem isn’t finished. Are they ever, really? But, at the moment I release the poem into the wild, it’s at least finished for now.

The rest is up to the reader.

I must accept that you may read these three incarnations and prefer any version. You may find the third to be stuffy and limited and the first to be freeing and friendly. You may think all three are garbage — I’m sure I will seconds after posting this.

What’s important here is that we’ve looked at how work is shaped and why. It’s a process not seen by those outside our disciplines, and because of that we are often underestimated.

We as artists, as creators, know that we are undervalued and underestimated by our larger society. What we create is viewed as having no practical use (translation: difficult to mass produce and monetize), and we are seen as people who step outside the norm to live a life of apparent frivolity and ego.

But we know that to create is to practice discipline. And this discipline requires an immense suppression of ego because we are beholden only to ourselves. There are no executives or managers requiring us to do things over, to edit and refine.

We have to push ourselves to make it happen, or it won’t happen at all.