JD Wilkes

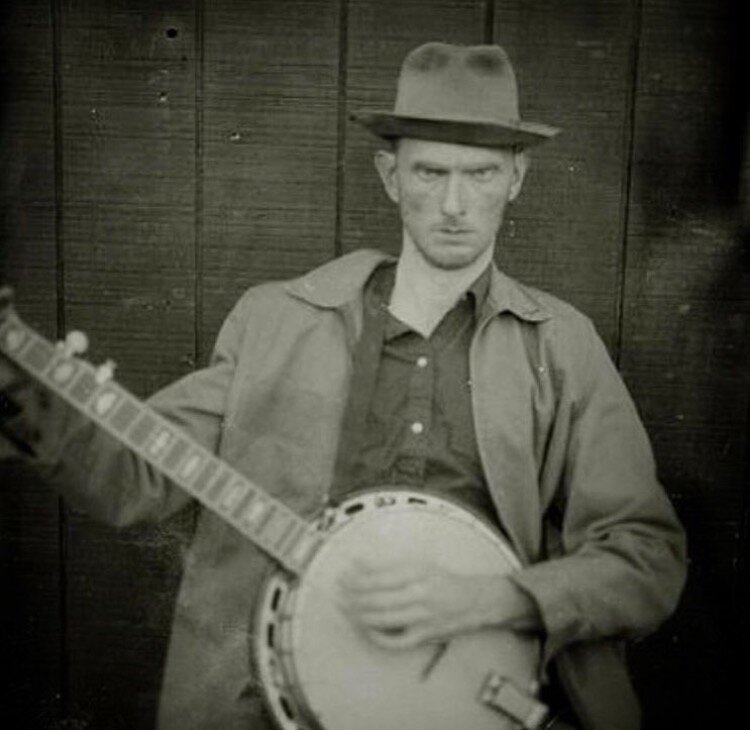

(photo by Max Cooper)

It’s nearly impossible to provide a succinct description of JD Wilkes to serve as an introduction. Much like the parable of the Blind Men and the Elephant, where each man could only describe the elephant by the part he came in contact with (a wall, a spear, a snake), Wilkes has so many facets that it’s difficult to encompass them all.

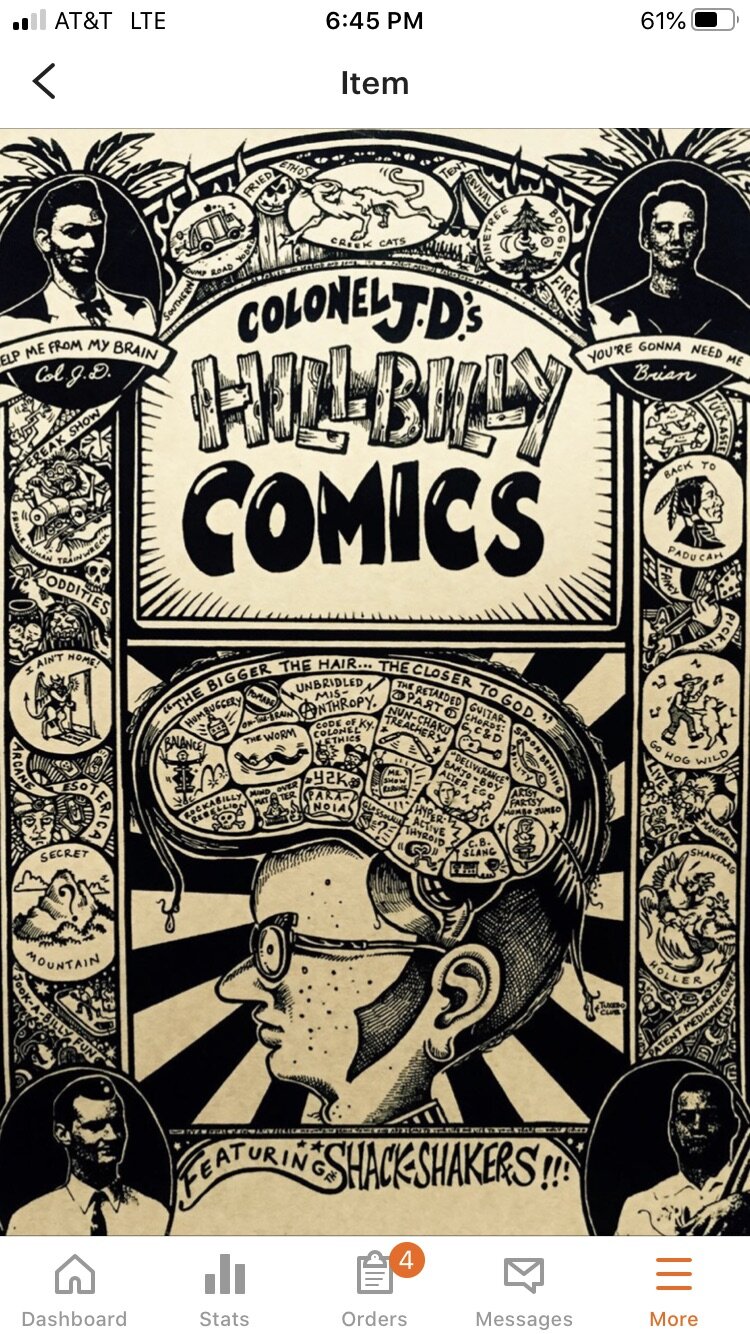

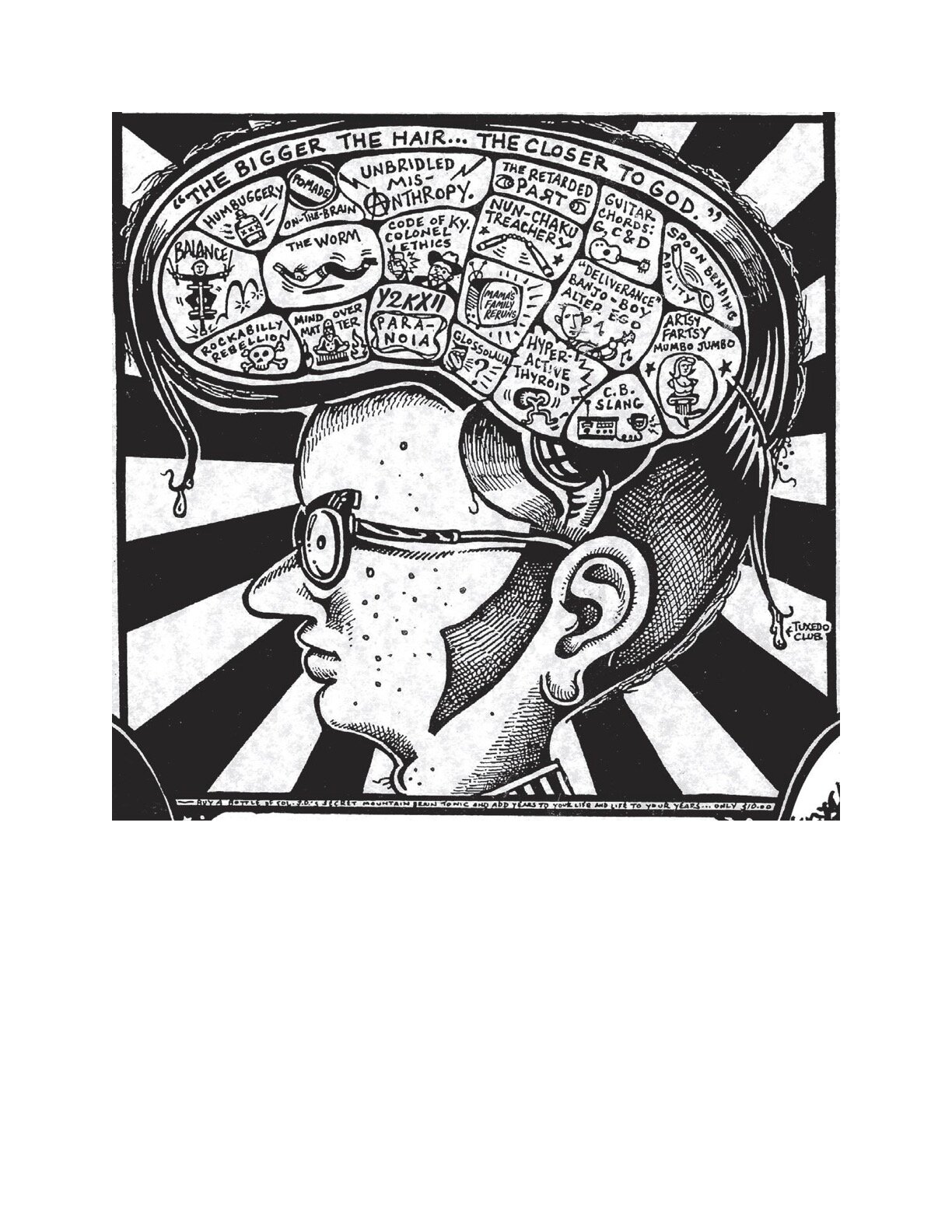

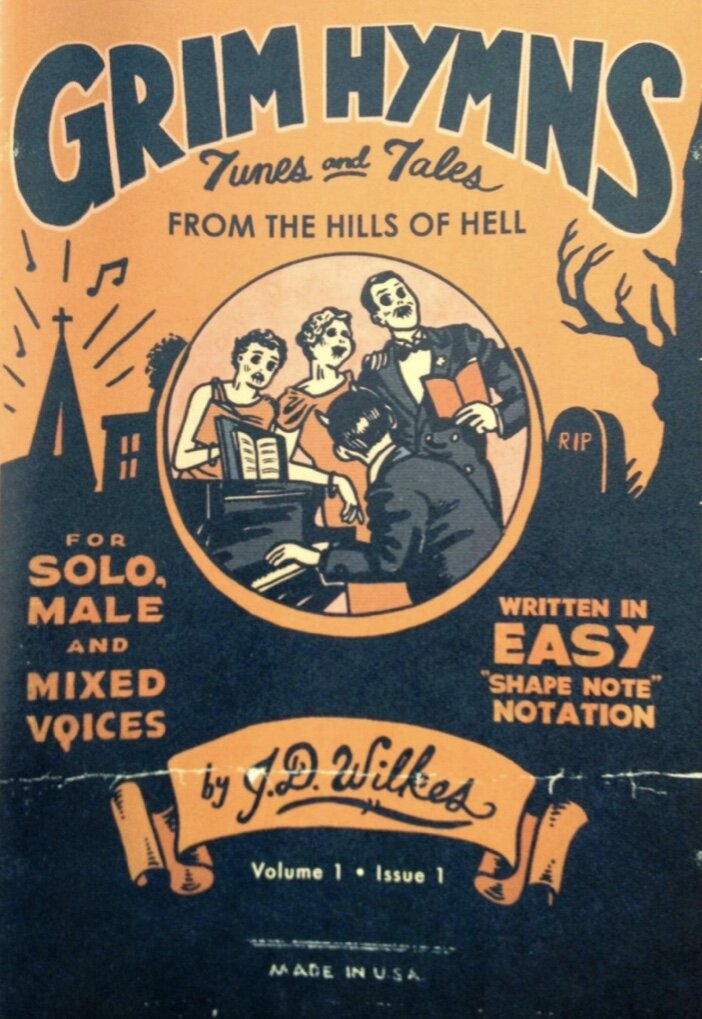

Part sideshow barker, part tent revival preacher, Wilkes is an artist cut from vintage cloth. A singer, songwriter, harmonica and banjo virtuoso, visual artist and novelist, Wilkes is born from the traditions of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and Tom Waits, of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, of Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis, of R. Crumb and Flannery O’Connor. Some see him as a psychobilly bluesman, others as a cartoonist, others as a Southern Gothic storyteller. In short, he’s a hillbilly renaissance man.

“I have musical and artistic ADHD,” Wilkes says. “I’ll promote whatever I’m feeling in the moment that will scratch the cathartic itch … I just keep these plates spinning according to my appetite.”

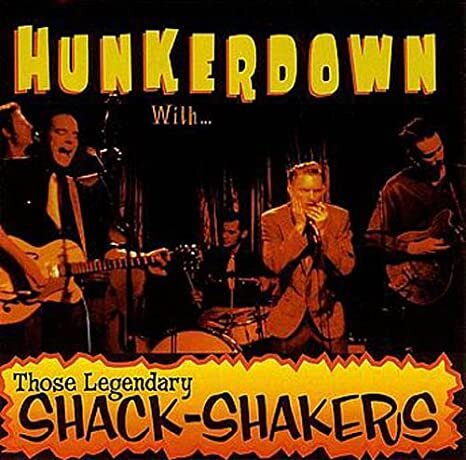

For 26 years now, JD Wilkes has been the frontman for the band the Legendary Shack Shakers, a blues-drenched and furious mongrel of rockabilly, jump blues and hillbilly music bristling with punk energy. And, although his degrees are in visual art, this sonic onslaught has laid the foundation for his career pursuing the most arcane tidbits of southern identity.

“The Memphis Flyer described the Shack Shakers as ‘holding dear what others discard,’” Wilkes says. “It was meant as a slam, but I’ll take it.”

His first musical love is the blues. “Muddy Waters is where everything changed,” he says. “I had convulsions the first time I heard it, like I was like Steve Martin in The Jerk, you know, ‘what it this music?!’ The Fathers and Sons double record, it just got me … made me want to be a harmonica player.”

As he began to perform, he veered slightly off the blues track. “I was getting into rockabilly because I didn't want to be a minstrel with blues,” he explains. “I never felt right because I hear white guys singing blues, and they put on that accent. But rockabilly you could be country and white and southern and ornery and a ham like me. Then you don't come across as like, this blackface thing, you know … No offense to some of those guys [who] are really good, and the great players, but whenever they sing it just sounds kind of phony, and I didn't want to do that.”

The Shack Shakers would go on to become an international phenomenon, touring incessantly and contributing to the soundtracks of True Blood, The Unit and more. Sturgill Simpson, the Black Keys, Robert Plant and Stephen King number among their fans.

His work across disciplines is widely varied, from satirical comics and sideshow banners to novels and deep dives into hillbilly music, but they all play in the same big swamp labeled, often lazily, Southern Gothic.

“There's all kinds of different Southern Gothic,” JD says. “Things like Faulkner — kind of stream of consciousness. Flannery O'Connor is kind of a Catholic cautionary … then you have Harry Crews and it’s almost like if the Jerry Springer show was in the ’70s. I just have a lot of interests, and I just pick what I like. I like reading classic Gothic literature … but I also like Moby Dick, and I like Saturday Night Live. I love Tolkien and stuff like that, and old fairy tales, the old Grimm tales, the color coded books that came out [The Junior Classics]. I just pick what strikes my fancy, and put them together to entertain myself. And then that ends up being what it is, and it's my flavor, I guess.”

(continued after photos)

He is currently working on a followup to his 2017 book, The Vine That Ate the South, that NPR’s Michael Schaub called a “bizarre, rollicking debut novel” and “relentlessly fun.” Where it was a kind of Grimm Brothers bestiary of southern tales of haints and heroes, this new book has a far more personal, and darker, genesis.

“This book I'm working on now started off as a nightmare journal,” he says. "Or dreams, or nightmares, but they were, you know, weird. Very little folklore in it at all. But I have to novelize those, and those are random, surreal things that you have to embellish or you have to change to where they'll fit together. And you’ve got to organize them where that makes sense. If this comes, you've got to put them in a sequence in order to normalize it. That's hard to do, because they're weird and unrelated. Right? That's where the challenge comes in. When you novelize it, then I've got to take that and somehow retrofit it to be a sequel to where I left off, and kind of match the tone of something that's completely different. And it’s using the same characters [as The Vine That Ate the South] to experience these things … but this is way, way weirder. I'm trying to make it more of a saga, or an epic Lord of the Rings kind of journey thing.“

There’s a paradoxical balance to his work. On one hand, it is a deeply distinct kind of specific southern identity with Wilkes’ frenetic personality as its figurehead. However, it’s also ecumenical in its embrace of folklore, style and humanity. Wilkes defies knee-jerk identity politics while embodying a deeper, more nuanced identity built on human experience and needs, but with outstretched arms, welcoming just about everything.

"I never had a group identity growing up,” he says. “I was always the nerd. So I was set free from worrying about it — they’d already said I don't count. So I'll just be over here in my own mind, playing. And it was kind of a relief. It was kind of the best thing ever happened to me, to be ostracized.”

Art is a refuge for people who don’t fit in. But it’s also a petri dish for cliques and cults with their own purity tests. “I always like to compare it to the Blind Melon video with the bumblebee girl.” Wilkes laughs. “I was the bumblebee girl literally in life looking for my bumblebee people. That's how the video ends. She finds her place. Well, every time I find my bumblebee tribe, there would be the same kind of jock attitude amongst them that I was trying to escape. That includes alternative music. Alternative country music, the Americana world, is all about like, ‘See I listen to this. I'm smart. This is your thinking person's country music.’ I call Emperor's New Clothes out on this stuff. I have no allegiance to any genre that the more I kiss ass, the more I will rise in the hierarchy … Pick out what rings true to you and be a well-rounded person. Whatever happened to that idea?”

By refusing to pledge allegiance to the stars of either the charts or Twitter, Wilkes is freed to build work that explores a south that runs deeper than social media “so you want to talk about” memes or headlines. Through the results of (and the people behind) the 2020 election in Georgia and districts across southern states, a more nuanced understanding of the south is beginning to grow — the south is not a monolith, and not easily reduced to red states. It’s complicated. It’s rich in culture, intelligence, diversity and ambition. And it’s breaking a new set of shackles — one built by racist gerrymandering, corrupt politicians, shady news and shadier preachers.

In his work, Wilkes gives us a south that bends under the weight of its horror while also celebrating a long and profound mingling of race, class and religion bound together by storytelling, food and music — a south that holds both these truths simultaneously.

“I wrote that barn dance book [Barn Dances & Jamborees Across Kentucky] … I needed to eject out of rock and roll and punk,” Wilkes explains. “You kind of get lost in, ‘Why am I doing this again?’ You forget. ‘Am I trying to be hip and popular? Am I trying to be rich or something? Am I saying the right stuff?’ I just took took a year off and went on a junket across Kentucky and just went to these places, these old-time, kind of like miniature versions of the Opry … and just listened and talked to and interviewed and wrote a book about, you know, jamborees and barn dances and things like that.”

“It was music made for music’s sake, without the hope of fame. And it was a refreshing thing for me to do. Square dances, fish fries, play parties and barn raisings and things like this that serve the small community — the souls of a small community. It's always served some sort of cathartic purpose for a community … rockabilly, and a lot of blues — and Piedmont blues especially — and bluegrass was a meeting of the races.”

He adds, “And that's that's why the South is so fascinating, because we're so cross-cultural. And we get all this shit talked about us. It's like, well, you know, yes, politically. Yeah, it's messed up. But so are you, Holland. I mean, let's talk about your past. You were the ones running the boats over. At least we made something out of this pain despite it all. The love between people of a similar class, different races, really enhanced culture and we get no credit for it. Like, the world has said, ‘we'll take that thanks.’ And then flips us off on the way out.”

Through his work with the Legendary Shack Shakers and his own solo music, through novels, barbed comics, sideshow posters and stories, Wilkes celebrates the broken, the outcast, the weird and the wild. He shows us again and again that the south itself is like the story of the blind men and the elephant — it’s big and complicated, and we’ll never define it by only looking at just one part.